Even John F. Kennedy had his paintings: how Ukrainian graphic artist Yakiv Hnizdovskyi conquered the world

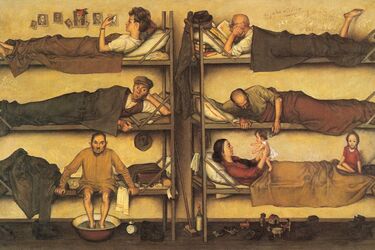

Yakiv spent half his life as a nomad. First Lviv, Warsaw, Zagreb, then Munich and the DP refugee camp. There were children, women, and the elderly. All together in an open area. Some died, and others were born instead. It was there that "Displaced Persons" appeared. A canvas with three-story bunks and six difficult fates. One refugee is twirling her curls because she is young and wants to get married, and another is playing with her baby. So, instead of houses, windows, wells, stoves, chests, or pots, there is only one single charpoy. This is the threshold, the atonement, and the images.

Eventually, he moved to America and settled in the unprestigious Bronx neighborhood, one popular among poor immigrants. He rented a cold closet and set out on his own, realizing that creativity requires a certain amount of freedom, not an office bell and blank walls. There was not enough money. He couldn't afford to pay for the services of a model, and he didn't have the words to negotiate with a person (he knew English only a little). Thus, his characters were sheep, orangutans, cats, zebras, turtles, geese, ducks, and flamingos, who posed for vegetables and peanuts. There were also sunflowers, cacti, tomatoes, beans, carrots, onions, and bare leafless bushes. He was lucky that there was a botanical garden and a zoo nearby, so he spent days threre. Every night, the police combed the paths with a flashlight because they knew that the eccentric bearded man was so engrossed in his sketches that he didn't hear the whistle.

Since then, cheap linoleum has replaced the blackboards, and an old burlap sack and a paint ladder have replaced the linen canvas and easel. The man became a regular customer of the shop, where torn sacks were sold for a few cents. He was quiet, thin, and had a distinctive announcer's voice. He avoided crowds and idle chatter. While working, he listened to the music of Bortnyansky and Vedel. At the end of the day, he would have a glass of white Spanish wine.

One day he went to Paris, and there was Stefania. She was a Ukrainian woman whose family had emigrated to France during the First World War. The girl was sewing dresses at the Christian Dior fashion house and felt confident, so she approached the modest artist and started flirting. She would say something like, "Since you're hanging out in Paris, what kind of Yakiv are you? You are a real Jacques now." Soon the young people got married and had Mira. The artist sold his "sheep" and bought his first house. He was forty-seven years old at the time.

The graphic artist and ceramist learned not to have any special desires. He worked in direct sunlight: in summer with a brush and in winter with a spoon or a sharp knife. When people asked him why he chose wood (since it was much easier to work on paper), he replied that he preferred to feel the resistance that only wood can provide. So he stocked up on cherry, pear, and apple trees. Despite his American citizenship, he identified as a Ukrainian and expressed desire to be buried at home, near familiar hills and orchards. During his lifetime, he had more than one hundred and fifty solo exhibitions, and "Winter Landscape" and "Sunflower" even decorated the oval office of John F. Kennedy in the White House. He created more than 300 engravings, 250 woodcuts, and hundreds of paintings. He illustrated the anniversary edition of Slovo (The Tale of Igor's Campaign). He was buried in the Lychakiv Cemetery (before that, he had been in line in the New York Columbarium for twenty years). At the time of reburial, a lump of his native Ternopil soil was placed on his grave.